8. Rossignol C Code

Oct 10, 2021 by Mr. Allen

“You must promise not to tell anyone about this, Daisy.”

“You must promise not to tell anyone about this, Daisy.” “I’m serious.”

"I promise."

She unlocked her office door with an ancient key, then knelt and, blocking my view, twisted the dial on the big safe. It made a low woof when the door swung open. We put on latex gloves. She fished a piece of paper from between two sheets of tissue, and handed it to me. It was old, but not as old, say, as some of the papyrus sheets my Dad has shown me, and it wasn’t very big, just a few inches. You could see crease marks in the paper where it had been folded, folded many times in fact, so it must have been easy to carry around in a small pocket, like a note that got passed around at school. The writing, in French, was very hard to make out because there were brown-tinted numbers written on top of them. The numbers were grouped in twos or threes like: “22 412 878, 21 331 125 146 21 893 428 87 991,” and so on.

“Were the numbers written in invisible ink or something?” I asked.

Aunt Mill looked pleased. “They were, yes. It’s an iron sulfate ink, developed with sodium sulfide. The writing in black ink was meant to mask the fact that there was an invisible message below.

“Is it for real? I mean it looks like spy stuff.”

“Very real. Written around the time of the French Revolution.”

“What’s it say?”

“I don’t know yet. That’s what I’ve been hired to find out. It’s like a big math puzzle.”

“Well, who wrote it?”

“That’s part of what I’m trying to determine. It was in a package of such things that came from the estate of a former British, um, security minister, in the early Nineteenth Century, a man in charge of keeping track of French émigrés and diplomats.

“Woah, so this is like in real secret code?”

“Yes. In Rossignol C code to be precise, or, well, as precise as we can be at this point.”

“Aunt Mill, this is so, so cool. Are all these papers in your safe secret messages?”

“No. Most are non-secret, but from the same time period, written by people we think may have been involved in some way. They might provide clues or even show us whose handwriting this is.”

“Who hired you to do this?”

“A man with a lot of curiosity and a lot of money.”

I looked at the paper again, squinting, trying to see if the numbers would tell me something, but of course they didn’t. “So are these orders to steal a secret formula or blow up a super weapon or something? You must know something about what it says.”

Aunt Mill smiled, considered a second and said, “Have you ever heard of Jeanne de Valois, Comtesse de la Motte?”

I shook my head.

“What about Queen Marie Antoinette?”

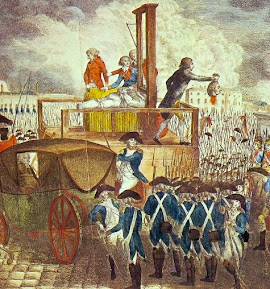

“Sure. She got her head cut off.”

“Indeed, she did. But before that she was involved, or maybe really not so involved, in what the French call, ‘the Affair of the Necklace,’ which some people say contributed to Marie Antoinette’s head becoming neck-less.”

“Cool.”

“And the Comtesse de la Motte, most believe, helped steal the necklace, a huge, magnificent thing, worth a king’s ransom, or, put another way, worth enough to buy a million loaves of bread for the starving people of Paris.”

“Did the Comtesse get away with it?”

“She did. She fled to London, wrote her memoirs, and lived happily ever after. Until someone pushed her out a window.”

“No way!”

"Aunt Mill laughed.